Reality cancelled.

Donald Hoffman makes a convincing case against reality, but I can’t embrace his theory.

Reading is such a joy, even when it isn’t. Recently, I experienced an example of this paradox with ‘The Case Against Reality: How Evolution Hid the Truth from Our Eyes’ by Donald D. Hoffman.

The book is nearly three hundred pages and in them, the author convincingly presents his theory that the world is nothing like our perception of reality, we experience an interface that interprets reality. It’s well written and clearly explains the proposition, yet reading it was not an entirely pleasant experience. I made a significant cognitive effort to comprehend the ideas and their implications. Worse, the reward for my effort were concepts that I find depressing.

The uncoupling of perception and reality isn’t a new idea: ‘Many sensations which are supposed to be qualities residing in external objects have no real existence save in us,’ said Galileo in the 17th century. ‘They reside only in the consciousness.’

In the 17th century, consciousness was thought to reside in the brain, in the 21st century Hoffman dismantles this by saying that quantum mechanics tells us that classical objects - including brains - don’t exist.

A key idea in his book is that our perceptions are honed by fitness, not truth. Evolution has given us the ability to perceive what we need to know to survive while hiding the additional complexities of reality that we don’t need to know. For example, humans can’t perceive nuclear radiation - in the world where we evolved there was no advantage in having that ability. Presumably, in a different world with strong localised areas of nuclear radiation we would have the ability to perceive it. How we might perceive it, according to Hoffman, would have no direct correlation with the reality of nuclear radiation. It might be a pink fog, a particular itching sensation on our skin, a specific type of smell or some other representation, like a snake. Evolution selects for fitness not reality.

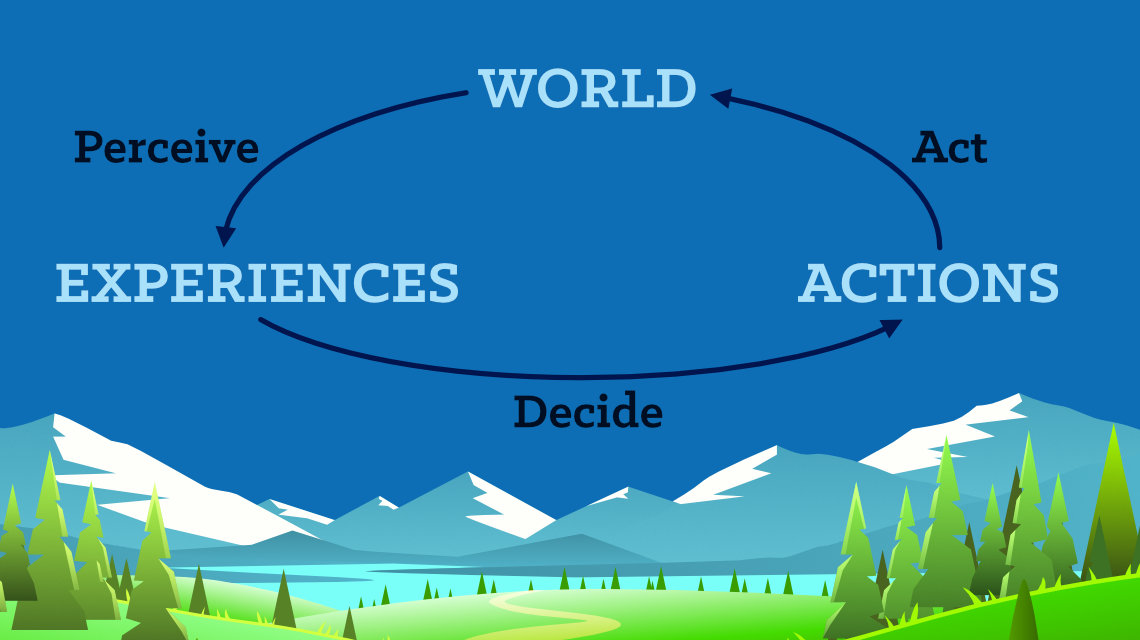

The idea that if we have to take something seriously, we also have to take it literally is wrong. A venomous snake can kill a human, that is an undeniable fact proven by experience. According to Hoffman that doesn’t mean the snake exists in the world, it is an icon that represents a real and life-threatening entity. The ultimate nature of reality is only the experiences we have and their outcomes, as illustrated by Hoffman’s ‘PDA loop’ (see diagram above). PDA stands for Perceive, Decide, Act. The PDA loop is a mathematical model of consciousness.

Here’s Hoffman explaining it, in a conversation with Amanda Gefter for Quanta magazine: “I have a space X of experiences, a space G of actions, and an algorithm D that lets me choose a new action given my experiences. Then I posited a W for a world, which is also a probability space. Somehow the world affects my perceptions, so there’s a perception map P from the world to my experiences, and when I act, I change the world, so there’s a map A from the space of actions to the world. That’s the entire structure. Six elements. The claim is: This is the structure of consciousness.”

Upsettingly, he later adds, “I can pull the W out of the model and stick a conscious agent in its place and get a circuit of conscious agents. In fact, you can have whole networks of arbitrary complexity. And that’s the world.”

When I look at snow-capped mountains against an intense blue sky, I feel good. The idea that I’m probably not seeing what is really there is upsetting. There is a part of me that acknowledges Hoffman’s ideas and is eager to learn more while another side rejects those same ideas and just wants to stare contentedly at the mountains and marvel at the blue sky. It’s an internal conflict that I could easily resolve by discarding these ideas I have been exposed to. Not easy. Hoffman is a professor in the Department of Cognitive Sciences at the University of California. For over thirty years he has studied consciousness, visual perception and evolutionary psychology using mathematical models and psychophysical experiments. He is a respected expert on the subject he writes about, a credible source with plausible theories.

My work has convinced me that belief is stronger than evidence because it is formed by need and desire. Consequently, I don’t regret having studied Hoffman’s theories but I chose to continue to believe that the mountains and blue skies that I love are real.