It's alive.

Last week saw the successful launch of my book and Mark Stinson asked me to talk about it, and creativity in general, on his podcast.

The Forces of Collaborative Creativity came out last week and gratifyingly, it went straight to number 1 in its category on Amazon in the USA and was number 1 for four consecutive days in Italy. My heartfelt thanks go to the many who bought the book and all those who supported the launch by helping to spread the word. One supporter was my friend and colleague Mark Stinson, who invited me to chat with him on his podcast ‘Unlocking Your World of Creativity’.

Please have a listen or, if you prefer, you can read a lightly edited transcript of the interview.

Mark: Was there a particular creative project that you worked on today that required your full creative attention?

Peter: Definitely, yes. I can’t go into details because I sign NDAs that will take away my firstborn and everything else if I talk about the work I do. But this one is a tool we are creating and that will help physicians have more meaningful conversations with patients. Due to the pandemic, a lot of communication is no longer face-to-face and that takes away a certain level of confidence and ability to talk about more emotional things. So we are developing a tool that helps doctors and patients have meaningful conversations and reveal things that need to be revealed in a particular scenario even when they're not in the same place.

Mark: Do you have a source of inspiration for when you are creatively stuck, what is a go-to stimulus for you to get your creative juices flowing?

Peter: There isn’t a single go-to thing, because to me only the most important thing to creativity is diversity and so whatever I did last time I want to do something different. I want to get a different perspective and so to me, it's all about being inspired by something different. I believe that all creativity is contextual. When you are creating it, the people you create with, the stimulus you have - that context influences your creativity. There is also the fruition of creativity which is contextual. Depending on who sees it, when they see it, why they're seeing it, what's their predisposition or expectation. And therefore all those variables, which are all stimulus, are all contextual. I think you just need to have very very diverse things stimulating you.

Mark: What about obstacles? Obviously in any creative endeavour faces some hurdles. How do you face those hurdles, manage them get around them, over them, through them?

Peter: I bulldoze the obstacles I can and I weave around the ones I can’t. I think the difference between a good, professional creative and somebody who may need a bit more experience is being able to differentiate between bulldoze mode and weave mode and getting it right. Because if you weave around something you should have bulldozed you are probably compromising something. I think that's the key.

Mark: So this, creative judgement. I’m just wondering that the creative mind could get blocked by these obstacles and frustrated and you are saying just push through?

Peter: Well you are talking about something slightly different. The idea of being frustrated as a creative being is wrong in my opinion and here’s why. If we are talking about a creative act which is self-inspired and self-produced then there are no obstacles, every single one of them can be bulldozed and if you don't bulldoze it that is your choice. If you are a creative doing applied creativity, you are doing it for money and you are doing it somebody else. If you mistake your realisation, your emotional reward, with what is actually a job then you're in trouble and I think you need to keep sight of the fact that job satisfaction is going paid and doing something well and being professional. The emotional realisation of creativity sometimes comes out of that, but don’t count on it. Which is why I think creatives in applied creativity should have personal projects. You should express yourself without barriers in your personal stuff.

Mark: That’s a very good point. So you're saying that the in the profession of creativity at a commercial level you still need this outlet for your creative energy that you control.

Peter: Yes. If you're going to see Bruce Springsteen in concert - and he's famous for like three hours of this really solid entertainment - you want to see Bruce Springsteen sing his songs the way you know he sings them. Now, he might not wake up that morning wanting to do that but he's gonna do it. If he wants to sing a Puccini opera in the shower before the concert (or write a new song) that’s how he expresses his creativity, that's his emotional release. Then gets up on the stage and performs his famous songs, for you.

Mark: That’s so true. Let’s dive into the book: The Power of Collaborative Creativity. I emphasise the word ‘collaborative’ because just as we were saying: many people think creativity is this talented individual, producing something all by themselves. Yet that is very rarely the case is it?

Peter: Very rarely. I think the idea of a sole creative talent producing something is closely tied to craft. People confuse creativity and craft. If you are a phenomenal sculptor the act of sculpting is both intellectually creative because you decide what you want to get out of the block of marble you are sculpting but it’s also the technique, the physical work and the effort you put into crafting that thing. The craft is not what we are talking about. What we are talking about is an intellectual activity and collaborative creativity is group intellectual activity. Sometimes the output is amazing ideas and sometimes it's not, because sometimes that's not the objective. One of the central things about the use of creativity in business is that you can use it for many many things. You don't have to use it just to have new ideas and new products or new ways of promoting products or whatever. You can use it to discover things about people, help people discover things about themselves, you can use it to get teams to work better together, understand each other better. You can use it to get consensus and alignment around issues which people have difficulty discussing and through creativity they can safely confront each other and then find a common ground.

Mark: I love the subtitle, that it’s a practical guide to bringing groups together. Because you’ve described some very lofty goals: we all want to work together, we want to have ideas but often groups and their facilitators don’t have the tools and the techniques to do that. It sounds like you are giving us some of that tool and technique kind of stuff.

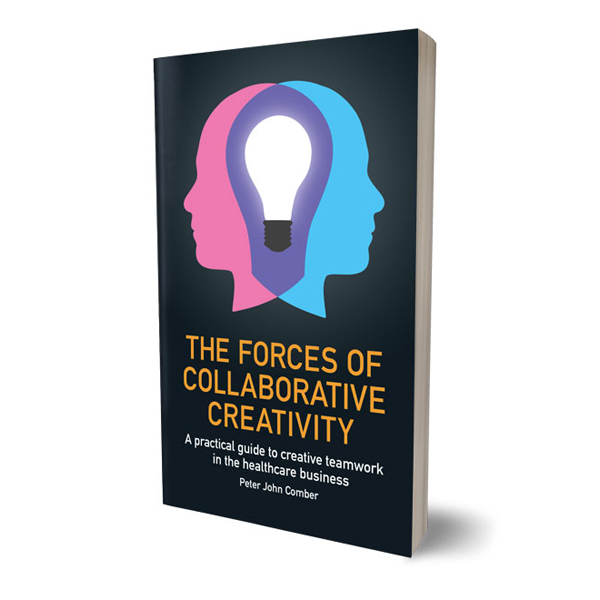

Peter: The book is in two parts. The first part of the book talks about what Collective Creativity is and when it's useful, why you should consider using it in a business and it gives you a general understanding of what the moving parts are. Part two of the book is absolutely a step-by-step guide on how to do this. Somebody with a minimum of experience of doing workshops, having read this book, could set up their own Collaborative Creativity session. Some of the exercises are already in there, it’s a very practical book.

Mark: So, you can pull it off the shelf, open it up and there you have a step-by-step guide?

Peter: Yes. Absolutely. However, there are so many variables - creativity, as I said before, is all about context, every time you do a different project, with different people, the context changes. So there isn't a completely automatic process. It needs a certain amount of interpretation, one of the things that’s fundamental about Collaborative Creativity is that all the exercises have to be tailor-made. When I say there are exercises in the book, I mean there are examples of types of exercises but for each of them I say you have to personalise it, you have to have to make it relevant to the people you want to do this exercise.

Mark: Let’s talk about the fun part of it. People often like to walk out of a meeting and say that was a lot of fun. Yet we have to balance that with the productivity, the output and ask if the meeting was effective. How do you find that balance?

Peter: By challenging people. The title of the book is The Forces of Collaborative Creativity and there are five forces: empathy, realisation, invention, cohesion and self-discovery. Invention is pretty obvious, it's what everybody thinks creativity is for. Realisation is much bigger than fun. Realisation is reward, it’s purpose, it’s people saying ‘Okay, I get what we are, why we are doing it and I’m happy with doing it. There is also Self-discovery: if you get people doing creativity for themselves, or others, quite often they learn a lot about themselves while they are doing it. That's far more effective than just fun. Fun is something that goes away, it becomes a nice memory, while self-discovery can change the way you act, in a positive way. It can change the way you think about the job you do and your colleagues. I've done sessions with all kinds of participants: physicians, specialists, patients, people who work in pharma - helping them to break down the silos within their companies. The really good sessions, the ones that worked well, everybody is exhausted at the end. The reason is that they’ve put a lot of effort into it and it's emotionally draining.

Mark: Yeah, brain work can be very physical. You reminded me of the, sometimes, unintended outcomes but teams really do have moments of self-realisation and empathy within the group and it ripples out far beyond the meeting and the exercise. This really does help anchor the team to a higher purpose.

Peter: Exactly. You’ve touched on something central to the book. I think the value businesses see in creativity is in a widget or something that they can take to market and monetise. What I try to point out is that there are byproducts of creativity and byproducts of the widget which are incredibly valuable. A team that learns how to work with each other while they are creating that widget and taking that widget to market - they are co-authors, they share the glory of the work. That is equally as valuable to the company because that team through that process learnt a lot about themselves, a lot about the market and learnt a lot about the way the company can function, which is not necessarily how it functions now. That is change, which is hard. There is so much you can get out of creativity if you just stop focusing exclusively on the widget.

Mark: So true. Then there's this idea of getting that creativity, the idea, out into the world. When we have to execute what are some of the forces of collaboration that come into play when you're actually producing the creative idea?

Peter: The thing that kills innovation and change more than anything else's is the not-invented-here-syndrome. Basically, if you and I come up with something we think is smart within a very big organisation as soon as we start taking it to people who didn’t come up with that idea they’re not going to look at that idea, necessarily, as good. Their attitude is going to be: ‘What have these two come up with, how is it going to affect me?’

If you involve all relevant stakeholders both internal and external basically you are killing within the creative process all the ideas which that group can't really process and can't really see value in and you are making sure that the idea that survives this group is an idea that the group wants to see win. They want to see it be successful. So if you’ve ever been in a situation where you work with a team and they’ve come up with something they’ve fallen in love with and then they've taken it to some other part of the company to get buy-in and that other part of the company has said ‘No’. Or they've modified it to so they feel very comfortable with it, basically taking the life out of it. This takes time and it's wasteful in terms of resources this method. So just get somebody to represent functions that can say no or modify it right from the start get their input, get them to build it with you. It will be a better product, it will get to the market in a better shape.

Mark: You are really giving us a behind the scenes glimpse of the creative process. I think a lot of people think there's this lightning bolt and then I’m supposed to come into your office and make you see why this is such a great idea. But you are turning this inside out, aren’t you?

Peter: It’s a question of likelihood and percentages. We all fall in love with the beautiful narrative of Steve jobs saying I'm going to invent the iPhone, I’m not going to ask anybody if they like it, I’m just going to make it the way it should be because I’m a visionary.

Mark: Yeah, we love the tale that there were no focus groups and everybody just fell in love with this thing.

Peter: Exactly, everybody falls in love with this thing and it changes the world! Alright, if that's what happened, fine, I’m not going to say it didn't but it's one in a million. The odds of that happening are so small as to be absolutely idiotic to try and do it. If you're in the business of not losing money and being successful you want to do it the smart way. You want to come up with things that you know the market is interested in and ready for, that your company is totally convinced, from top-to-bottom, is needed and can be done well by that company. I always say that the best strategy isn't the best theoretical strategy, it's the best strategy your company can and will deliver.

Mark: That’s exactly right. Terrific book, I can’t wait to read it in detail. But give us a glimpse of your creative process of actually writing the book. How was the process for you?

Peter: Well, you’ve written a lot of books so you know more about this than I do. I can only talk about this book and the background is that I am not a writer. Creatives broadly speaking fall into two categories: the people who write and the people who doodle. I started my life in the doodle camp and lived happily like that for many years!

Mark: Doodling pays well!

Peter: Yes, but it's not a transferable skill when you want to write a book. So the actual writing of the book was difficult for me, I have to admit. In terms of putting down on a page, the process that I use and my company uses it wasn't that hard. The difficult part was generalising because what I discovered in writing the book is that we are always used to applying our methodology in specific situations. When we have a client or a project that is well-defined and that allows you to be quite precise in the way you explain it and you organise it. When you write a book you have no idea of the situation the person who can pick up that book is in. You have to generalise so much that it became uncomfortable for me. The opposite of generalisation is writing a book that is so dense with specific variants according to various situations that it's boring and impenetrable. I actually wrote this book twice. I wrote the first draft of the book tried too much to address all the variables and was, frankly, a mess. It was hard to read because there were so many almost contradicting things; so the second version of the book was simplified. I accepted I would have to make a sweeping generalisation and live with it.

Mark: There is a certain courage to looking at your own work and saying this needs to be redone.

Peter: Yes, but I think one of the transferable skills of doodling and spending a lot of time working in applied creativity is that you do have the instinct to make everything as simple as you can. So I think the first draft was a means for getting all the information out and the second draft was about making something coherent and reasonably easy to understand.

Mark: Like you said before when it's your own personal passion there’s a different set of motivations and drivers. You’re not trying to meet a client brief or deadline.

Peter: Interestingly, one of the big things that changed between the first draft and second is that I sent the first draft to clients and colleagues and asked them to read it and give me their feedback. The book wouldn’t be as good as it is if I haven't had those people giving me their points of view and their opinions it really was incredibly valuable so the only piece of advice I would give somebody is if you want to write a book okay do it. But before you try and publish it get somebody who knows your subject to read it and tell you what they think - it has to be somebody who cares enough to actually tell you the truth.

Mark: You’re applying that same collaborative philosophy even in creating your own book. It’s like, I need to get the customer’s feedback to be sure I’m communicating something worthwhile.

Peter: It’s two different worlds. I think people need to understand that if you're writing a novel that's your vision and nobody can say that the idea on page 3 is wrong or right. That’s your thing. But if you're trying to do something which is helping people, which is explaining something or doing something that pertains to a business venture you have to make yourself aware of what your audience thinks and needs. This book explains a methodology while also explaining what our company does. In that context it isn’t a question of what you want to do, it’s a question of what people understand and it goes back to that thing about context.

Mark: As we close, talking of context, I’d like to ask about Milan, where you live - more than famous for creative inspiration and history. Do you derive some of that inspiration for yourself from your environment?

Peter: Definitely. I think one of the worst effects of covid, for me, has been the fact that museums have been closed and theatres have been closed. I think one of the joys of living in a city is that there's so much cultural offering. To be creative I think you need diverse stimulus and I think the only way to get diverse stimulus is to go out and see what's going on. Being in a city makes that relatively easy because there is so much on offer. Right now there’s not that much going on. I went to see a very beautiful exhibition on Georges La Tour but it was hard to get tickets because they're only allowing very few people into the exhibition at any given time and the whole process of getting in, with temperature measurements and the distancing, once inside takes a little bit of the poetry out of it. In normal conditions, I think being in a city, especially in a big city with the relevant cultural history is a big plus if you're a creative.

Mark: Peter, thanks for a great conversation, I really enjoyed it and all the best with the new book.

Peter: Well thank you very much, Mark. It’s been an absolute pleasure.