Wide-eye impact.

Terence Conran’s death, on September 12, has prompted me to look back on his influence on British culture.

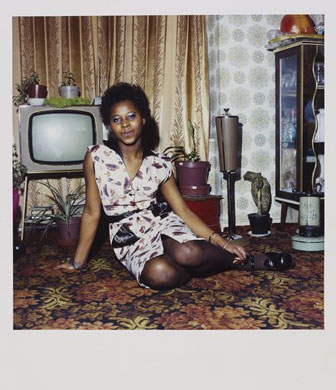

If you weren’t there at the time, it is hard to imagine how revolutionary certain things were when they happened. In the early 1960s, the inside of the average British home was overstuffed and gloomy: patterned wallpaper; robust dark-wood furniture; damask pattern sofas and couches; dark carpets and curtains whose functionality was still psychologically linked to the blitz-imposed black-outs. Ornaments, vases, plates and cutlery were often of Victorian and Edwardian styles. Design elements, created for the vast spaces of stately homes, were crammed into the poky rooms of millions of two-up and two-downs. The image below, taken in 1972, nicely exemplifies the aesthetic of a typical British interior of the '50s, '60s and '70s.

Image: Neil Kenlock, ‘Untitled [Young woman seated on the floor at home in front of her television set]', C- type print, London, 1972: © Neil Kenlock / Victoria and Albert, London.

Now, if the above has enlightened you or reminded you of the prevailing style, it is easier for you to see the jump to what came next. Today, the interior of the average Briton’s home has a modernist look that could be described as Ikea-cool, because the Swedish company has proven hugely successful at making this style accessible to the masses. The break, from the fussy past to the minimalist present, was pioneered by Terence Conran and it began on May 11, 1964, when he opened the first Habitat store, on London’s Fulham Road. The Habitat look, like so many popular successes, was not particularly original. It heavily copied Bauhaus modernism and contemporary design trends, including Danish design which was influential at the time but, and this is important to understand, most people weren’t aware of these styles and if they were they thought it ‘wasn’t for them’. Modernism and design were considered pretentious and silly. Jacques Tati makes delicious fun of modernism in his film Mon Oncle (1958) and amusingly captures the prevailing (petit-bourgeois) sentiment towards it. Today design is mainstream, in the early '60s it was not, and Terence Conran deserves merit for this change. I believe that his greatest contribution to design in Britain was to make the subject interesting and accessible to a mass audience.

My earliest memories of the house I grew up in are of a hardcore 1950s interior with accents from the ’20s and ’30s. I can only vaguely remember the changes over the years that chipped away at the old look but I do remember the 50-50 patchwork of old and new styles that it displayed in the early '80s when I abandoned it. In between, I also vividly remember visiting the Habitat stores with my mum and how exciting it was. The objects displayed were so sleek and unadorned compared to what I lived with every day that they seemed alien. My kind of alien. These were artefacts of a very different civilisation and it was one I wanted to be a part of. I couldn’t know it at the time but they were a glimpse of the future. Conran made us want that future he made it hip enough without it being far out. He made domestic beauty egalitarian. He said he priced his products to be accessible to “someone on a teacher's salary".

In the ’60s and ’70s, Terence Conran rode a giant wave. The young generation was relatively affluent and desperate for change. Post-war austerity in Britain had strangled investments and consequently stifled certain types of progress. So yes, the sixties would have been a time of change regardless of Conran’s contribution and design would probably have emerged into popular relevance regardless. What set Habitat apart was that it didn’t really sell furniture and home decor, it sold a vision of a different life. Conrad was a marketer and a brand-builder (he did as good a job with the Terence Conran brand as with Habitat). He was a lifestyle influencer before they even existed, with a magpie’s eye and cosmopolitan taste.

Not all his business moves were successful and, in 1990, Conran was forced to resign as chairman of the corporation that had grown out of the success of Habitat, acquiring over time many other iconic British high street brands. A testament to his sensibility and vision is that once a bunch of managers had control of his stores, they put the tat (as in ‘tatty’) in Habitat. Design populism works only when it isn’t condescending. Of course, many of those weened onto design by Habitat progressed to the ‘real-thing’ - original manifestations of great design with a price tag to match. But the cool-design-for-all blueprint was solid and when Ikea radicalised the do-it-yourself practicality of mass-produced flat-pack furniture - that Habitat had pioneered - it became ubiquitous. In 1991, IKEA bought the Habitat brand.

I have read that Ingvar Kamprad once said to Conrad, “When will you learn to take care of what you already have?” I think maybe the answer is that he couldn’t, he was too much of a creative-man and not enough of a businessman. Apparently, as a child, he chased butterflies, precociously feeding his fascination with collecting beautiful things. I like to think that he chased, and caught, butterflies his whole life. It may not be the ideal characteristic of a successful businessman but I think it made his life interesting and rewarding. It is certainly what allowed him to have such a huge impact on me in my formative years when he shared with a drab, grey-brown nation his colourful collection.